Battle of Cape Matapan

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle of Cape Matapan (Greek: Ναυμαχία του Ταίναρου) was a World War II naval battle fought from March 27 to March 29, 1941. The cape is on the southwest coast of Greece's Peloponnesian peninsula. A force of British Royal Navy ships accompanied by several Royal Australian Navy ships, under command of British Admiral Andrew Cunningham, intercepted and sank or severely damaged the ships of the Italian Regia Marina under Admiral Angelo Iachino.

The opening actions of the battle are also known in Italy as the Battle of Gaudo.

Contents |

Orders of battle

The Allied force was the British Mediterranean fleet, consisting of the aircraft carrier HMS Formidable, the modernised World War I battleships HMS Barham, Valiant and Warspite (as flagship). The main fleet was accompanied by two flotillas of destroyers:

- 10th Flotilla: HMS Greyhound, HMS Griffin and HMAS Stuart commanded by Commander Hec. Waller, RAN

- 14th Flotilla: HMS Jervis, HMS Janus, HMS Mohawk and HMS Nubian commanded by Philip Mack

Also present were HMS Hotspur and HMS Havock.

A second force, under Admiral Sir Henry Pridham-Wippell, consisted of the British light cruisers HMS Ajax, HMS Gloucester and HMS Orion, the Australian light cruiser HMAS Perth and the British destroyers HMS Hasty, HMS Hereward and HMS Ilex.

The Australian HMAS Vendetta had returned to Alexandria.

In addition, Allied warships attached to convoys were available: HMS Defender, HMS Jaguar and HMS Juno waited in the Kithira Channel and HMS Decoy, HMS Carlisle, HMS Calcutta. HMS Bonaventure and HMAS Vampire were nearby.

The Italian fleet was led by Iachino's vessel, the modern battleship Vittorio Veneto. It also included almost the entire Italian heavy cruiser force: the Zara (under Vice-Admiral Carlo Cattaneo), Fiume and Pola; four destroyers of the 9th Flotilla (Alfredo Oriani, Giosué Carducci, Vincenzo Gioberti and Vittorio Alfieri). The heavy cruisers Trieste (carrying Vice-Admiral Luigi Sansonetti), Trento and Bolzano were accompanied by three destroyers of the 12th Flotilla (Ascari, Corazziere and Carabiniere), plus the light cruisers Luigi di Savoia Duca Degli Abruzzi (Vice-Admiral A. Legnano) and Giuseppe Garibaldi and nine destroyers of the 6th Flotilla (including Emanuel Pessagno and Nicoloso de Recco). None of the Italian ships had radar, although several Allied ships did.

The 10th and 13th Flotillas of Italian destroyers, the Alpino, Bersagliere, Fuciliere, Granatiere, Grecale, Libeccio, Maestrale and Scirocco, were also involved.

Background

As ships of the Mediterranean Fleet covered troop movements to Greece, intelligence was received reporting the sailing of an Italian battle fleet with one battleship, six heavy and two light cruisers plus destroyers to attack the convoys. The interception was made possible by Ultra decryptions of intercepted signals, but, as ever, this was concealed from the enemy by ensuring there was a plausible reason for the Allies to have detected and intercepted the Italian fleet. In this case, it was a carefully directed reconnaissance plane. As a further deception, Admiral Cunningham is said to have made a surreptitious exit from a club in Egypt to avoid being seen going on board ship.

At the same time, there was a failure of intelligence on the Axis side. The Italians had been wrongly informed that the Royal Navy's Mediterranean Fleet had only one operational battleship. In fact there were three, and a lost British aircraft carrier had been replaced.

The battle

On March 27, Vice-Admiral Pridham-Wippell with the cruisers Ajax, Gloucester, Orion and the Perth and destroyers sailed from Greek waters for a position south of Crete. Admiral Cunningham with Formidable, Warspite, Barham and Valiant left Alexandria on the same day to meet the cruisers.

The Italian Fleet was spotted by a Sunderland flying boat at noon, thus Iachino lost the adavantage of surprise. The Italian Admiral also learned that the carrier Formidable was at sea thanks to the decryption team aboard the Vittorio Veneto. Nevertheless, after some discussion, the Italian headquarters decided to go ahead with the operation, in order to show the Germans their will to fight and confident in the higher speed of their warships.[2]

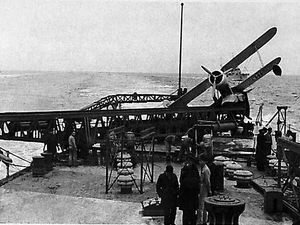

Action off Gavdos

On March 28, an Ro.43 launched by the Vittorio Veneto spotted the British cruiser squadron at 6:35. At 07:55, the Trento group encountered Admiral Pridham-Wippell's cruiser group south of the Greek island of Gavdos. The British squadron was heading to the southeast. Thinking they were attempting to run from their larger ships, the Italians gave chase, opening fire at 08:12 from 22,000 metres. The Italian guns had trouble grouping their rounds, which had little effect. The rangefinders also performed poorly, with the exception of the Bolzano's. After an hour of pursuit, the Italians cruisers broke off the chase and turned northwest, under orders to rejoin the Vittorio Veneto. The Allied ships also reversed course, and followed the Italians at extreme range. Iachino's plan was to lure the British cruisers into the range of the Vittorio Veneto guns.

At 10:55 the Vittorio Veneto met the Italian cruisers, and immediately opened fire on the shadowing Allied cruisers. She fired 94 rounds from a distance of 23,000 meters, all well aimed, but with the usual excessive spreading of her individual salvoes. The Allied cruisers, until then unaware of the presence of a battleship, withdrew, suffering slight damage from 381 mm shell splinters.[3] A series of photographs, showing the Italian salvoes falling around the British warships and taken from HMS Gloucester, was published by Life magazine on 16 June 1941.[4]

Air attacks

By this point Cunningham's forces, which had been attempting to join up with Pridham-Wippell's, had launched a sortie of Fairey Albacore torpedo bombers from HMS Formidable at 9:38. They attacked the Vittorio Veneto without direct effect, but the required manoeuvring made it difficult for the Italian ships to maintain their pursuit. Realising that they might not be so lucky next time, Iachino broke off the pursuit at 12:20, retiring towards his own air cover at Taranto.

A second sortie surprised the Italians at 15:09. Lieutenant-Commander Dalyell-Stead flew his Albacore to 1,000 metres from Vittorio Veneto, hitting her outer port propeller and causing 4,000 tons of water to be taken on. The ship stopped while damage was repaired, but was able to get underway again at 16:42, making 19 knots. Cunningham heard of the damage to the Vittorio Veneto, and started to pursue her. Dailyell-Stead and his crew were killed when their aircraft was shot down.

A third strike, by six Albacores and two Swordfish from 826 and 828 Squadrons on Formidable as well as two Swordfish from 815 Squadron on Crete was made between 19:36 and 19:50. A torpedo, apparently dropped by Lieutenant F.M.A. Torrens-Spence, crippled the cruiser Pola, forcing her to stop. Unaware of Cunningham's pursuit, a squadron of cruisers and destroyers were ordered to return and help Pola, formed on the Pola's sister ships, the Zara and Fiume. The squadron did not start to return towards Pola until about an hour after the order been given by Iachino, officially due to communication problems, while the Vittorio Veneto and the other ships continued to Taranto.[5]

Night action

The Allies detected the Italians on radar shortly after 22:00, and were able to close without detection. Italian ships were not supposed to meet enemy ships by night and had their main gun batteries disarmed; they also had no radar and could not detect British ships by means other than direct sight, so the British battleships Barham, Valiant and Warspite were able to close to 3,500 metres unnoticed by the Italian ships, from where they opened fire. The Allied searchlights illuminated their enemy. Some British gunners witnessed the cruiser's main turrets popping up dozens of metres into the air. After just three minutes, two Italian heavy cruisers, the Fiume and the Zara, had been destroyed. Fiume sank at 23:30, while Zara was finished off by a torpedo from the destroyer HMS Jervis after midnight.

Two Italian destroyers (Vittorio Alfieri and Giosué Carducci) were sunk in the first five minutes. The other two destroyers, Gioberti and Oriani, managed to escape, the former with heavy damage. Towing Pola to Alexandria as a prize was considered, but it was getting light and it was thought that the danger of enemy planes was too high. The British boarding parties seized a number of the much needed Breda anti-aircraft machine guns.

Pola was eventually sunk with torpedoes by the destroyers Jervis and Nubian after her crew had been taken off. The only known Italian reaction after the shocking surprise was a fruitless torpedo charge by some destroyers and the aimless fire of one of Pola´s 40 mm guns in the direction of the British warships.

The Allied ships took on survivors, but left the scene in the morning, because of Axis air strikes. Admiral Cunningham ordered a signal to be made on the Merchant Marine emergency band. This signal was received by the Italian High Command. It informed them that due to air strikes the allied ships had desisted in rescue operations. It granted safe passage to a hospital ship for rescue purposes. The location of remaining survivors was broadcast and the Italian hospital ship Gradisca came to recover them.

Allied casualties during the battle were a single torpedo bomber shot down by Vittorio Veneto's 90 mm anti-aircraft batteries, with the loss of the three-man crew. Italian losses were up to 2,303 sailors, most of them from Zara and Fiume.

Aftermath

After the defeat at Cape Matapan, the Italian fleet never again ventured into the Eastern Mediterranean until the fall of Crete. The Italian naval command lost all faith in German promises to protect their fleet from attack here. Hence, Cape Matapan was an important strategic victory for the Allies who could now concentrate most of their stretched resources against the Afrika Korps in North Africa under General Rommel after the fall of Greece to German forces in late April 1941.

Despite his impressive victory, Admiral Cunningham was somewhat disappointed with the failure of the destroyers to make contact with the Vittorio Veneto. The escape of the Italian battleship was, in the words of the British Admiral, "much to be regretted".[6]

There is still controversy in Italy regarding the orders given by the Italian Admiral Angelo Iachino to the Zara division in order to recover the Pola, when it was clear that an enemy battleship force was steaming from the opposite direction.

Order of battle

Italy

![]()

- Ammiraglio di squadra Angelo Iachino

- 1 battleship: Vittorio Veneto (damaged)

- 4 destroyers (10a Squadriglia Cacciatorpediniere): Grecale, Libeccio, Maestrale, Scirocco

- 4 destroyers (13a Squadriglia Cacciatorpediniere): Alpino, Bersagliere, Fuciliere, Granatiere

- Commodore Antonio Legnani

- 2 light cruisers (8a Divisione Incrociatori): Luigi di Savoia Duca degli Abruzzi, Giuseppe Garibaldi

- 2 destroyers (6a Squadriglia Cacciatorpediniere): Emanuele Pessagno, Nicoloso da Recco

- Admiral of Division Sansonetti

- 3 heavy cruisers (3a Divisione Incrociatori): Bolzano, Trento, Trieste

- 3 destroyers (12a Squadriglia Cacciatorpediniere): Ascari, Carabiniere, Corazziere

- Admiral of Division Carlo Cattaneo

- 3 heavy cruisers (1a Divisione Incrociatori): Fiume (sunk), Pola (sunk), Zara (sunk)

- 4 destroyers (9a Squadriglia Cacciatorpediniere): Vittorio Alfieri (sunk), Giosué Carducci (sunk), Vincenzo Gioberti, Alfredo Oriani

Allies

![]()

![]()

Force A, 14th Destroyer Flotilla, 10th Destroyer Flotilla (of Force C), Force B, 2nd Destroyer Flotilla, Force D

- Admiral Andrew Cunningham

- 3 battleships: HM Ships Barham, Valiant & Warspite

- 1 aircraft carrier: HMS Formidable

- 9 destroyers: HM Ships Greyhound, Griffin, Jervis, Janus, Mohawk, Nubian, Hotspur & Havock and HMAS Stuart

- Admiral Henry Pridham-Wippell

- 4 light cruisers: HM Ships Ajax, Gloucester & Orion and HMAS Perth

- 3 destroyers: HM Ships Hasty, Hereward & Ilex

- AG 9 convoy (from Alexandria to Greece)

- 2 light cruisers: HM Ships Calcutta & Carlisle

- 3 destroyers: HM Ships Defender & Jaguar and HMAS Vampire

- GA 8 convoy (from Greece to Alexandria)

- 1 anti aircraft cruiser: HMS Bonaventure

- 2 destroyers: HM Ships Decoy & Juno

- 1 merchant ship: Thermopylæ (Norwegian)

See also

Media related to Battle of Cape Matapan at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Cape Matapan at Wikimedia Commons

References

- ↑ Rivista Maritima (Italian)

- ↑ Greene & Massignani, pp. 148-150

- ↑ Greene & Massignani, pp. 150-151

- ↑ "Matapan: British fleet won sea victory over Italians"

- ↑ Greene & Massignani, pp. 152-156

- ↑ Brown, David (2002). The Royal Navy and the Mediterranean: November 1940-December 1941. Routledge, p. 76. ISBN 0714652059

- Greene, Jack & Massignani, Alessandro (1998). The Naval War in the Mediterranean, 1940-1943, Chatam Publishing, London. ISBN 1861760574.

- Royal Navy Website history section, Battle of Cape Matapan

- Regiamarina.net Operation Gaudo & Battle of Cape Matapan

- Historynet.com Battle of Cape Matapan

External links

- (English) "Battle of Cape Matapan: World War II Italian Naval Massacre" by Anthony M. Scalzo at HistoryNet.com

- (Italian) Battaglia di Gaudo at Plancia di Comando

- (Italian) La notte di Matapan at Plancia di Comando